When California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a variety of changes for the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 in October, it created an update to the most comprehensive privacy law currently in the U.S.. This new law is certain to have impact well beyond the California borders, just as the EU’s GDPR rules are changing behaviors of companies all over the world, including the U.S..

For example, Microsoft on Monday (Nov. 11) has already decided to extend CCPA rules across the country.

“Our approach to privacy starts with the belief that privacy is a fundamental human right and includes our commitment to provide robust protection for every individual,” Microsoft said in its blog announcement. “This is why, in 2018, we were the first company to voluntarily extend the core data privacy rights included in the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to customers around the world, not just to those in the EU who are covered by the regulation. Similarly, we will extend CCPA’s core rights for people to control their data to all our customers in the U.S..”

Although none of the specific changes are surprising or monumentally different from the initial version of the bill—this is a good look at the revisions, along with these two more detailed dives into the tweaks (which were then proposed but are now law)—it prompted us to look into revised law itself and we found nine items that the security compliance community needs to consider.

1) “A business that receives a verifiable consumer request from a consumer to access personal information shall promptly take steps to disclose and deliver, free of charge to the consumer, the personal information required by this section. The information may be delivered by mail or electronically, and if provided electronically, the information shall be in a portable and, to the extent technically feasible, readily useable format that allows the consumer to transmit this information to another entity without hindrance.”

Focus on the end of that passage, the part where it requires electronic communications to be in a “readily useable format that allows the consumer to transmit this information to another entity without hindrance.” That sounds a lot like ASCII plain text and it specifically sounds like it would ban any HTML pages designed to block copy and paste.

Ease of access is a wonderful thing, but when the data is ultra-sensitive (think medical lab results, a payment card’s purchase history, a series of bank transactions, etc.), compliance regulators may have concerns about this.

2) “The act prohibits a business from discriminating against the consumer for exercising any of the consumer’s rights under the act, except that a business may offer a different price, rate, level, or quality of goods or services to a consumer if the differential treatment is reasonably related to value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data. This bill would, instead, prohibit a business from discriminating against the consumer for exercising any of the consumer’s rights under the act, except if the differential treatment is reasonably related to value provided to the business by the consumer’s data.”

This sentence starts off by saying that an enterprise can’t punish a consumer for exercising their rights under the act. So far, so good. But it then lists a whopper of an exception: “except that a business may offer a different price, rate, level, or quality of goods or services to a consumer if the differential treatment is reasonably related to value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data.”

Charging a different (presumably higher) price is indeed a punishment aka a discrimination. The same with offering a different—again, presumably higher—rate, level or quality of goods or service. The only limit to those exceptions is that the “differential treatment” must be “reasonably related to value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data.” The value of the data to the consumer—which is what they reference—is entirely determined by the consumer. How is an enterprise supposed to calculate that?

The safest compliance route is to simply never punish a customer for using their rights under the California law. Doing anything different is inviting trouble, if not from California than from the FTC or other states and agencies.

3) “The act excludes publicly available information, as defined, from the definition of personal information and excludes both consumer information that is deidentified, as defined, and aggregate consumer information, as defined, from the definition of publicly available. Thus, the act does not exclude, as publicly available information, any consumer information that is either deidentified or aggregated. This bill would, instead, exclude consumer information that is deidentified or aggregate consumer information from the definition of personal information.”

First, our compliments for the most confusing phrasing of any paragraph known to exist. For comprehension’s sake, would suggest ignoring the first few sentences and focus instead just on the last one: “This bill would … exclude consumer information that is deidentified or aggregate consumer information from the definition of personal information.”

This is giving enterprises another out, but there’s an argument to be made to not take California up on it.

Let’s first look at aggregated. Generally, aggregated techniques often never collect the identifying data, so it’s relatively safe in that it’s almost impossible for someone to later figure out anything specific on any one customer.

But California’s definition doesn’t see it that way. California now defines aggregated as “information that relates to a group or category of consumers, from which individual consumer identities have been removed, that is not linked or reasonably linkable to any consumer or household, including via a device.”

“Been removed” is quite different from “never collected.” If someone is strictly abiding by California’s definition, meaning that they collect identifying data and then, at some later point, remove it, there is a non-trivial risk of it later being identified back to a specific customer. As long as that risk exists, it would be wise to share that with a customer who asks. Oversharing generally doesn’t invite compliance trouble.

The state’s definition of “deidentified” is even more problematic: “Information that cannot reasonably identify, relate to, describe, be capable of being associated with, or be linked, directly or indirectly, to a particular consumer, provided that a business that uses deidentified information. Has implemented technical safeguards that prohibit reidentification of the consumer to whom the information may pertain. Has implemented business processes that specifically prohibit reidentification of the information. Has implemented business processes to prevent inadvertent release of deidentified information. Makes no attempt to reidentify the information.”

The same concern exists here. It assumes that all mechanisms to remove the identities work and that no third-party programs (iTunes backup, for example, or an automated backup approach, such as in a crash analytics manner) undermine those efforts. In short, that’s a lot to assume. Isn’t it simpler to play it safe and share that information with the consumer as well?

4) “This section shall not require a business to retain any personal information collected for a single, one-time transaction, if such information is not sold or retained by the business or to reidentify or otherwise link information that is not maintained in a manner that would be considered personal information.”

The reference to “a single one-time transaction” seems to say that if collects sensitive data, then it has to shared or if it doesn’t, it doesn’t. But that’s true for multiple transactions as well. It sounds like someone meant to offer a specific exemption for a one-time transaction, but then forgot to actually do so.

5) “A business shall not discriminate against a consumer because the consumer exercised any of the consumer’s rights under this title, including, but not limited to, by: (A) Denying goods or services to the consumer. (B) Charging different prices or rates for goods or services, including through the use of discounts or other benefits or imposing penalties.” (And then, two sentences later:) (b) (1) A business may offer financial incentives, including payments to consumers as compensation, for the collection of personal information, the sale of personal information, or the deletion of personal information. A business may also offer a different price, rate, level, or quality of goods or services to the consumer if that price or difference is directly related to the value provided to the business by the consumer’s data.(2) A business that offers any financial incentives pursuant to this subdivision shall notify consumers of the financial incentives pursuant to Section 1798.130.(3) A business may enter a consumer into a financial incentive program only if the consumer gives the business prior opt-in consent pursuant to Section 1798.130 that clearly describes the material terms of the financial incentive program, and which may be revoked by the consumer at any time.(4) A business shall not use financial incentive practices that are unjust, unreasonable, coercive, or usurious in nature.

The law says that a business cannot discriminate by charging different prices or rates. And then lists a variety of ways that it can do just that. And then it adds into this contradictory section that “a business shall not use financial incentive practices that are unjust, unreasonable, coercive, or usurious in nature.” Unjust and unreasonable from which perspective? The consumer’s or the enterprise’s?

6) “Disclose and deliver the required information to a consumer free of charge within 45 days of receiving a verifiable consumer request from the consumer. The business shall promptly take steps to determine whether the request is a verifiable consumer request, but this shall not extend the business’s duty to disclose and deliver the information within 45 days of receipt of the consumer’s request. The time period to provide the required information may be extended once by an additional 45 days when reasonably necessary, provided the consumer is provided notice of the extension within the first 45-day period.”

This is pretty clean cut. Although it stresses 45 days for responding to the consumer and delivering the sought information, it then makes it clear the deadline is actually 90 days “when reasonably necessary.” Given how backlogged and overworked most enterprise staff is, this seems an impressively low bar to clear.

7) “Disclose the following information in its online privacy policy or policies if the business has an online privacy policy or policies and in any California-specific description of consumers’ privacy rights, or if the business does not maintain those policies, on its internet website and update that information at least once every 12 months.”

The key takeaway: Even if nothing significant has changed, the new California law requires updating the online privacy policy “at least once every 12 months.” That’s not bad advice but it’s now mandatory.

8) “A business that willfully disregards the consumer’s age shall be deemed to have had actual knowledge of the consumer’s age.”

This is an especially dicey compliance minefield. If your enterprise is giving site visitors any chance anywhere to provide contact information (to sign up for alerts, newsletters, product discount alerts, a heads-up when a deliver is imminent, etc.), you have a strong incentive to ask for age.

Even though people (especially under-age people) will often lie about their age, at least you have it on record that they said they were 25. That can prove helpful if that site visitors turns out to be 12 and you accepted their mobile information. The twist here is that if you don’t ask about age at all—which the law is now interpreting as “willfully disregards the consumer’s age”—you will be treated as though you knew the kid was only 12. In short, you really want to ask.

9) “A business may provide personal information to a consumer at any time, but shall not be required to provide personal information to a consumer more than twice in a 12-month period.”

With the obvious acknowledgement that “shall not be required to” is quite different from “thou shall not,” this gives enterprises an out with repeat requesters. Still, there are circumstances where it would make sense for a company to use this out sparingly.

For example, what if the enterprise has brought in different advertisers/partners and has repeatedly changed its privacy policy to allow for different kinds of data-sharing. A regulator could argue that each change merited an additional query for customers.

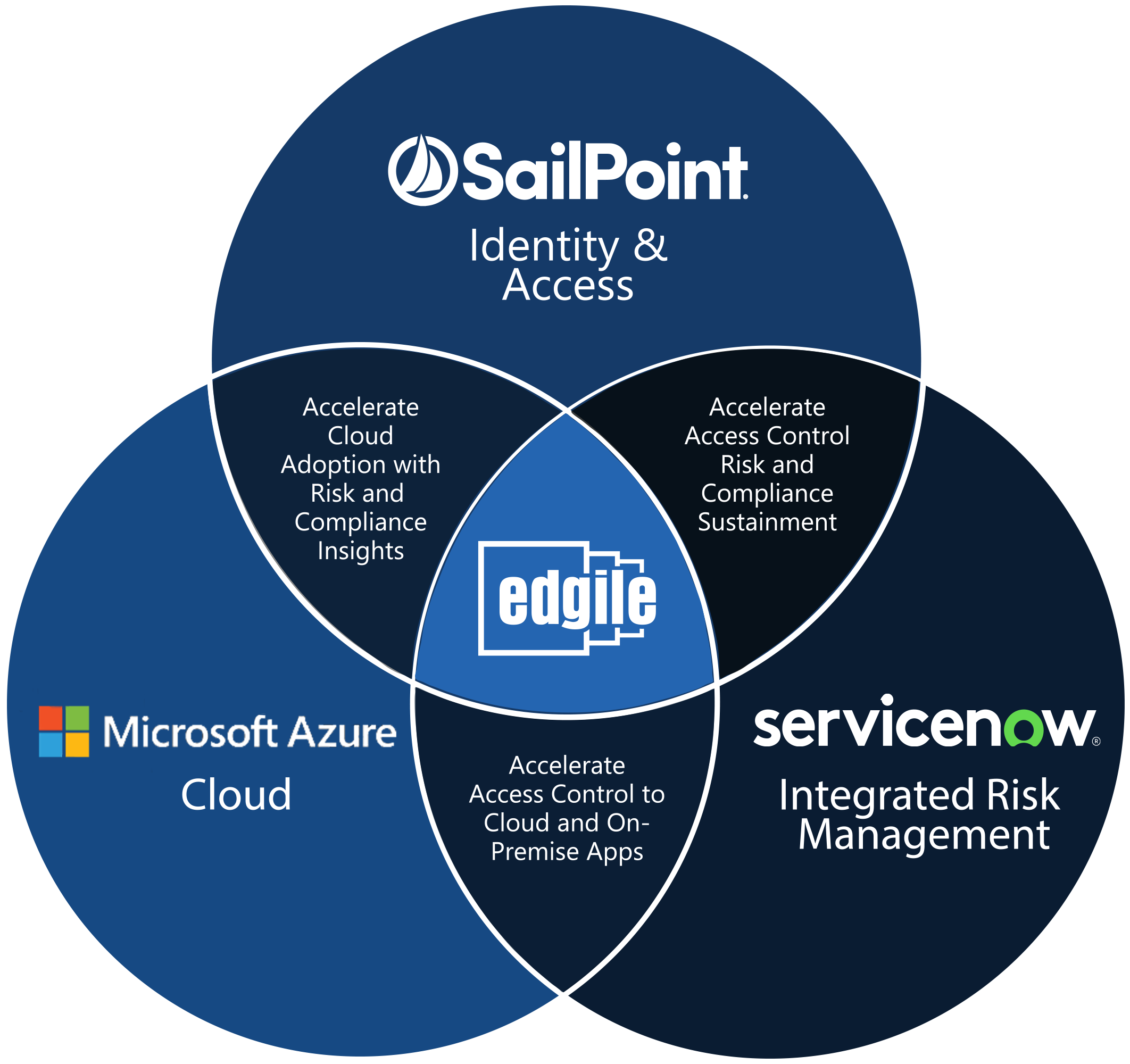

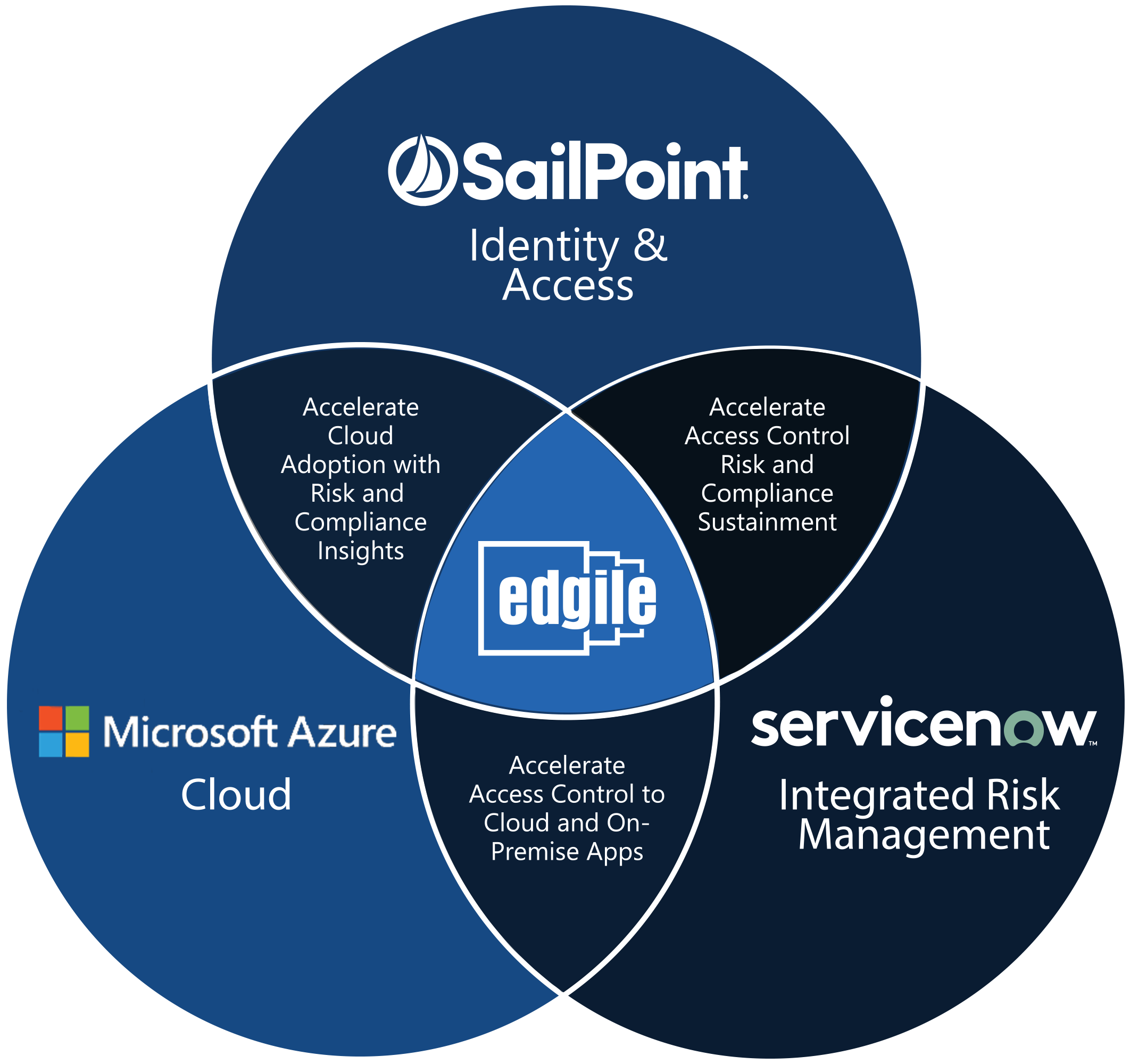

To learn more, please contact your Edgile rep or contact us here. We’ll be happy to help you navigate these newly-treacherous waters.