When two U.S. senators—one Democrat and one Republican—introduced legislation to update the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in March, it was the first major attempt at overhauling the law. But if it’s enacted as written, it would also bring new compliance requirements..

The legislation, for example, would change the current rules—which only protect children younger than 13—and adds protection for those 13-15 years old. The legislation would prohibit “Internet companies from collecting personal and location information from anyone under 13 without parental consent, and from anyone 13 to 15 years old without the user’s consent.”

First, not so sure that “Internet companies” has much meaning in 2019 given that the vast majority of companies—and certainly all large enterprises—have a Web presence.

Secondly, what would prevent someone younger than 13 from simply saying that he/she is 13-to-15 years old, thus eliminating the need to obtain parental consent? How many kids already misrepresent their age in order to access restricted websites?

The legislation attempted to address this by listing several authentication options—including enter in payment card data, provide a government-issued ID, “verify a picture of a driver’s license of other photo ID submitted by the parent and then comparing that photo to a second photo submitted by the parent, using facial recognition technology” and “answer a series of knowledge-based challenge questions that would be difficult for someone other than the parent to answer.” It also offered that someone could “connect to trained personnel via a video conference.”

But many of these approaches are not practical if the child says that he/she is 14 and chooses to say that he/she consents. The problem here is there exist very few reliable cost-effective means to verify the age of someone too young to have any of those identification documents.

If the legislation had simply said “collecting from anyone who claims to be 13-to-15,” it would have been fine as a company can prove what someone said. Given the lack of age-verification methods, enterprises must carefully articulate their consent mechanisms online, so that they can later defend this approach to regulators. The FTC, for example, places extensive weight on a company doing what it says.

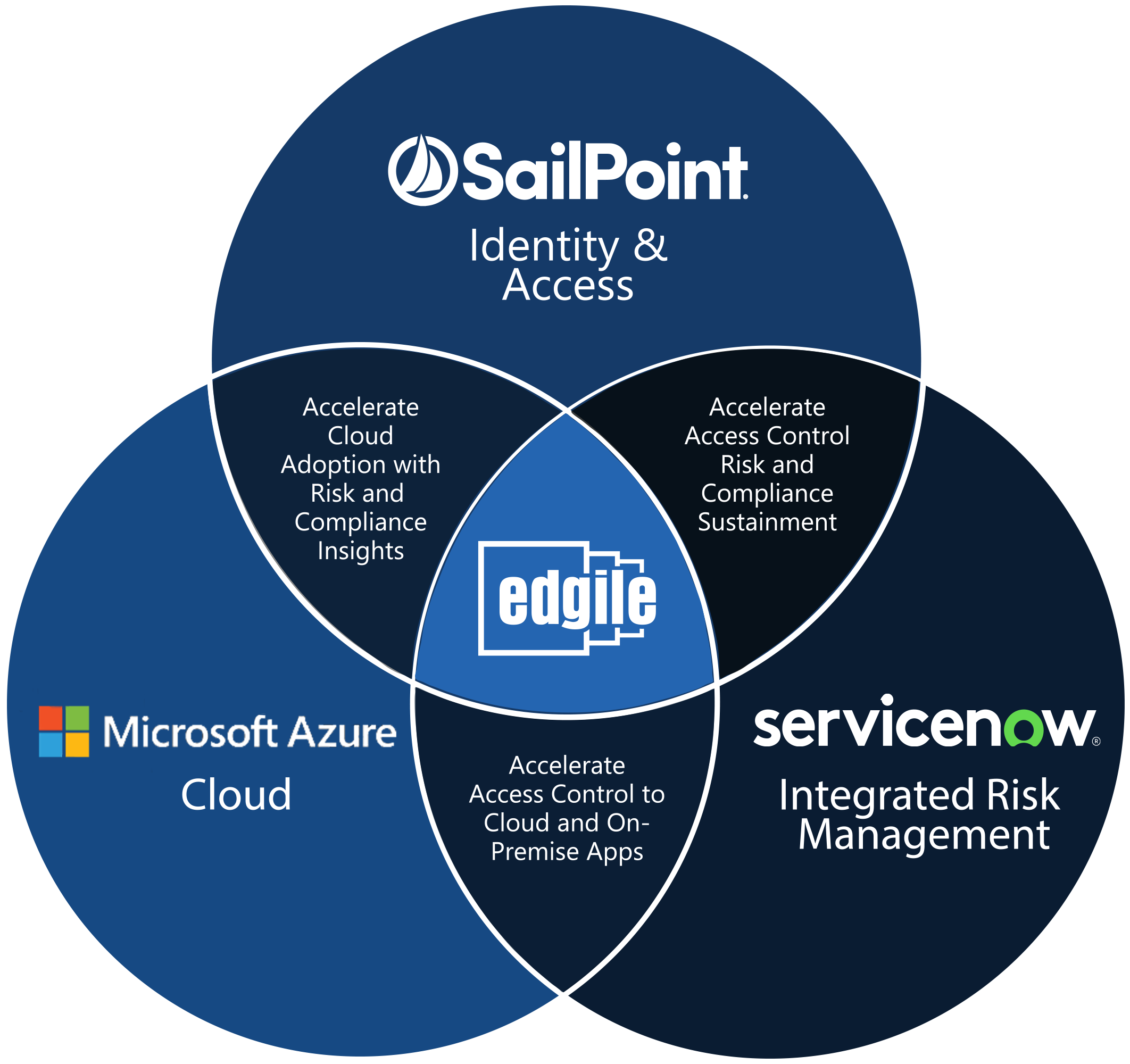

Edgile’s experience dealing with all manner of regulators helps us understand the phrasing and details that will most effectively help with compliance, especially with age-related issues.

The proposed legislation also directs the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to “create cybersecurity and data security standards for different subsets of connected devices based on the varying degrees of cybersecurity and data security risk associated with each subset of connected device.” In short, compliance requirements would vary from device to device, which will add extensive new complexities to this already-complicated law.

But this can be an opportunty rather than a problem. These rules will force enterprises–for their own good–to understand the varying degrees of risk associated with all devices and set policies and procedures accordingly. Documenting these efforts in details should sidestep any compliance problems.

Additionally, the statute would require manufacturers of connected devices directed to minors to display on the packaging for the connected device a “standardized and easy-to-understand privacy dashboard” describing how personal information is collected, transmitted, retained, used, and protected, and providing additional prescribed information, thus providing a direct path to regulatory compliance with these devices.

The proposed bipartisan legislation requires companies to implement mechanisms that allow users to “at any time delete personal information collected from the child.”

This raises two issues. First, today’s systems—especially with the cloud—make complete deletion of every copy of a piece of information almost impossible. What if an employee copies some of that data to a laptop and works on it at home? And what if they use Carbonite at home and a copy lands on a Carbonite cloud?

Aside from all of those issues—mostly dealing with backups, shadow IT, cloud and mobile devices, along with employees who grab a copy and don’t tell anyone—what if the company shares this data with various partners?

The best approach here is to have an explicit internal process for dealing with a good-faith effort at removing this data, a process that needs to be scrupously detailed to regulators.

The “constructive knowledge” standard (which would replace the actual knowledge standard) creates additional risks for the business. A conservative interpretation of this term would push businesses to adapt their privacy and information collection practices based on the assumption that any user of its website, application, etc., is a child. This creates more unnecessary costs to the business as most visitors to many sites are adults.

Targeted advertising to children would be banned, requiring companies that engage in this practice to change their business models. This could force some businesses to cease altogether or resort to other means of generating revenue (paywall?) to replace lost advertising dollars.

Would some businesses attempt to move away from content readily identifiable as “directed to a child or minor” in favor of more subtle advertising approaches to appeal to the youth market (think Joe Camel) in an attempt to avoid the compliance requirements of COPPA?

From a regulatory perspective, COPPA is not expecting perfection. Enterprises that examine their age-related policies and detail their new processes and procedures will do well as long as they make the arguments why these are reasonable approaches given the nature of the enterprise. Edgile has extensive experience here and can help.