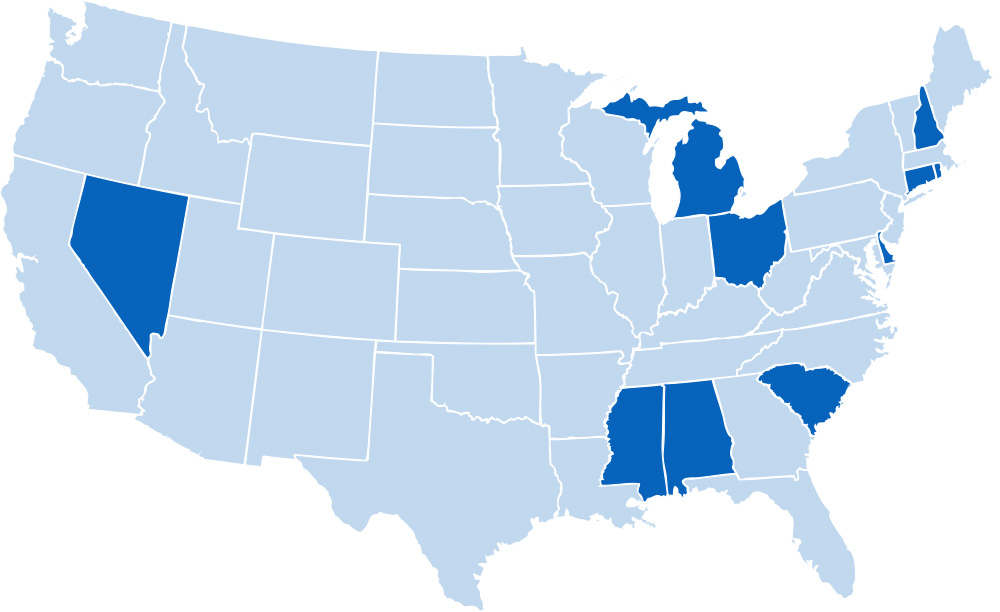

In 2019, when Connecticut, Delaware and New Hampshire enacted their versions of the National Association Of Insurance Commissions (NAIC) Insurance Data Security Model Law, they joined a half-dozen other states that have either adopted a version of NAIC (South Carolina, Michigan, Ohio, Mississippi and Alabama) or are seriously considering doing so (Rhode Island and Nevada).

From a compliance perspective, though, the NAIC model law is a bit of a contradiction. It’s raison d’être is compliance consistency, on the rationale that having one template copied by lots of states will make compliance easier by allowing one set of rules across the country.

But given that state legislatures have, thus far, made various tweaks to the phrasing, these laws are not nearly as consistent as was intended. The phrasings are similar enough state to state to encourage companies to treat them as the same, but they are in fact not. It’s the little changes that could prove risky to compliance efforts.

CONSISTENCIES

Let’s start with what, thus far, appears to have maintained consistency:

- Establish and maintain a comprehensive, risk-based written information security program and designate one or more persons or entities to be responsible for the program;

- Conduct a risk assessment to identify reasonably foreseeable threats that could result in “unauthorized access, transmission, disclosure, misuse, alteration, or destruction of nonpublic information” and assess the likelihood and potential impact of the identified threats;

- Assess the sufficiency of existing policies, procedures, information systems, and other safeguards to manage the identified threats;

- Implement information safeguards to manage the identified threats, and, at least annually, assess the effectiveness of the safeguards;

- Monitor, evaluate, and adjust the information security program;

- Ensure the licensee’s Board of Directors (if the licensee has one) exercises appropriate oversight of the information security program;

- Establish a written incident response plan designed to promptly respond to, and recover from, a cybersecurity event;

- Conduct a prompt investigation upon the occurrence of a cybersecurity event and maintain records concerning all cybersecurity events for at least five (5) years from the date of the event;

- Notify the designated insurance authority and affected consumers of a cybersecurity event which meets defined criteria, within specific time frames;

- Exercise due diligence in selecting third-party service providers and require them to implement appropriate measures to protect and secure information systems and nonpublic information accessible to them; and

- Certify compliance with the act on an annual basis and maintain all supporting documentation for five (5) years.

INCONSISTENCIES

Although most of the provisions set forth in each state’s adaptation of the Model Law track

- the original NAIC model version, there are some significant differences, such as:

- the time period for providing notice following a cybersecurity event;

- the potential monetary penalties for non-compliance;

- the maximum number of employees which would qualify a licensee for exemption from certain statutory requirements;

- the date(s) upon which specified requirements become enforceable (generally, the primary effective date of the statutory scheme is followed by a delayed enforcement date for implementation of a comprehensive written information security program, and a further delayed enforcement date for requirements pertaining to the selection and oversight of third-party service providers).

Entities subject to any of the noted statutory regimens are advised to review their information security programs and data breach notification policies and procedures to ensure compliance with all specified requirements and remediation of any gaps by the compliance deadlines. It will be insufficient to use the NAIC Model Law itself as the exclusive source of new requirements.

Rather, the specific modifications among the noted states’ versions of the Model Law require a detailed review of each relevant statutory regime. Compliance with one state’s requirements does not equal compliance with another state’s requirements. Businesses are encouraged to incorporate the strictest requirements from all relevant statutory regimes to ensure compliance across all jurisdictions.

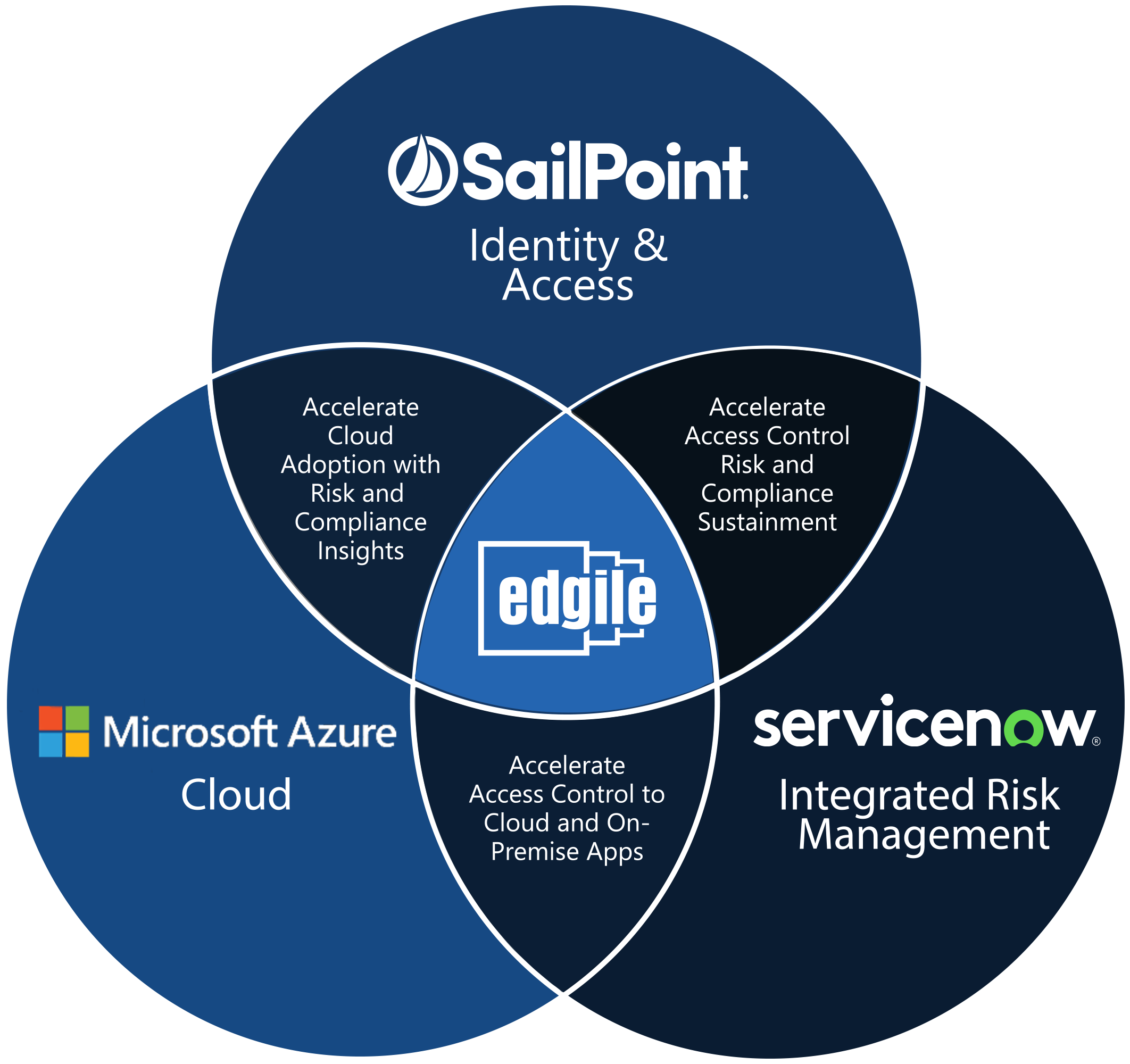

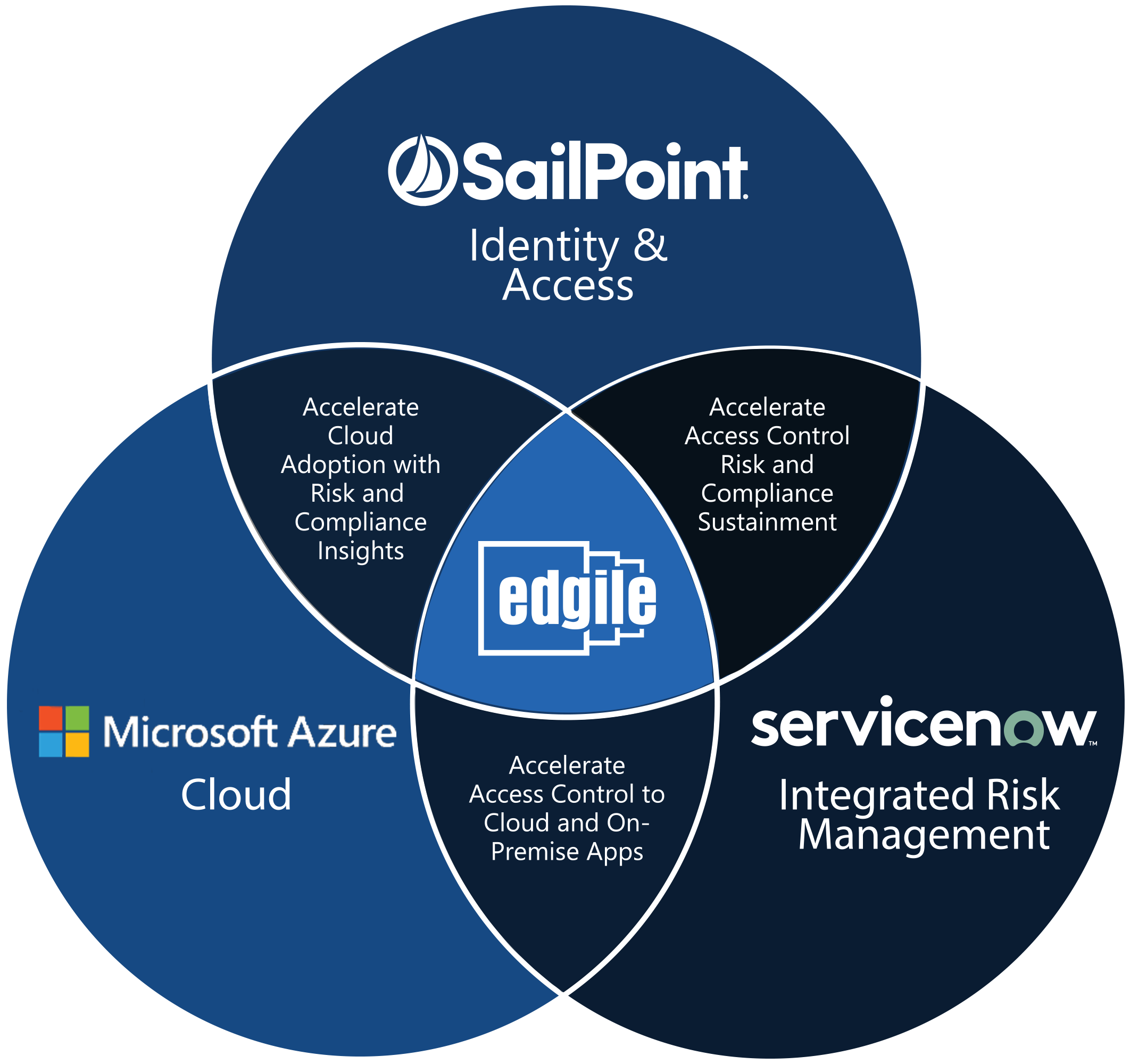

All of the states’ versions of the NAIC Insurance Data Security Model Law are included in Edgile’s Authoritative Sources Library as of Q3 2019. Edgile will continue to monitor developments on the adoption of the NAIC Model Law by other jurisdictions and will note any significant variations in the enacted schemes.

The Model Law is largely based on the cybersecurity principles set forth in the NYDFS Cybersecurity Requirements for Financial Services Companies (23 NYCRR 500) and establishes cybersecurity requirements for entities required to be licensed or registered under an adopting state’s insurance laws.

As stated by the NAIC, “The NAIC model law development process helps provide uniformity while balancing the needs of insurers operating in multiple jurisdictions with the unique nature of state judicial, legislative and regulatory frameworks.” The goal of the process is to harmonize the legal framework for insurance regulation across all states. To this end, once a model law has been adopted by the NAIC, state legislatures or regulatory authorities are encouraged to enact it with minimal changes.

CHANGES FOR CYBERSECURITY RULES

But the Model Law itself—along with some customized tweaks that some states are adding—are quietly changing the cybersecurity compliance requirements.

For example, Michigan’s new definition of “cybersecurity event” excludes unauthorized access to data by a person if the person acted in good faith in accessing the data and the access was related to the person’s activities. Presumably, this was designed to stop security research from forcing a company to declare a cybersecurity event.

But this raises some critical questions. Remember Robert Tappan Morris, who, when he was a grad student back in ’88, launched the first high-profile Internet worm and crashed much of the Internet? He was also the first person convicted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986. He was also researching security issues and testing limits, with no criminal intent. How many victims of that attack would classify it as anything other than a cybersecurity incident?

When determining whether an incident is reportable, isn’t the damage that resulted from an attack far more germane than the thinking of the person who perpetrated it? This isn’t an issue of legal liability for the attacker–a very separate issue with very different requirements–but of the obligations of the victim.

ENCRYPTION ISSUES

There are also interesting definitions from within the NAIC model law. Consider: “The term Cybersecurity Event does not include the unauthorized acquisition of encrypted nonpublic information if the encryption, process or key is not also acquired, released or used without authorization. Cybersecurity event does not include an event with regard to which the Licensee has determined that the nonpublic information accessed by an unauthorized person has not been used or released and has been returned or destroyed.”

This impressively overstates unwarranted confidence in a company’s ability to know precisely what an attacker did or will do and also understates the ability of a thief to do difficult things, such as bruteforce encryption cracking.

Some would argue that when nonpublic information is stolen, it’s a cybersecurity incident meriting reporting. Yes, it’s wonderful that the stolen data is encrypted, but no encryption is perfect and it can be broken, with enough skill, time and compute-power.

It also says the incident doesn’t have to be reported if the decryption key was also not stolen. First, how can a CISO/CSO be so sure the key wasn’t stolen? Secondly, what if the key wasn’t stolen during the incident, but the thieves left themselves a backdoor to steal the key one week from now? Anything that is encrypted can theoretically be decrypted.

We now have the second part of that exclusion: “Cybersecurity event does not include an event with regard to which the Licensee has determined that the nonpublic information accessed by an unauthorized person has not been used or released and has been returned or destroyed.”

Forensic analysis is a wonderful and initial effort, but this phrasing assumes perfection. Ask any veteran security forensic analyst and they will tell you that any analysis is a best attempt to piece together what happened, based on clues left behind. The better thieves are at covering their tracks, the less complete and precise that forensic picture will be. Indeed, forensic reports done immediately after an attack’s discovery will often differ from such reports performed three months later. These things take time—lots of time.

Also, this language about “has been returned or destroyed” is troubling. When it comes to data, what does it mean for a thief to return the data? Is that returning the data or returning access to the data, as in a ransomware attack? If it’s returning a copy of the data, what makes anyone think the thief didn’t keep a copy? It terms of reporting obligations, a thief returning data should have zero impact.

Then we have to deal with whether a CISO “has determined that the nonpublic information accessed by an unauthorized person has not been used or released.” This falls under the heading of proving a negative which, simply, can’t be done.

If the investigation finds a copy of the stolen data—especially coded bait data that was fabricated in the database to track it—on the Dark Web, yes, the company can conclude that it was used or released. But what could possibly justify the opposite conclusion, that the stolen nonpublic information was not used by the thief? Short of finding and arresting the thief and fully examining all of the thief’s records and systems, it seems impossible.

BREACH NOTIFICATION DIFFERENCES

Another significant difference involves the notice deadline following a cybersecurity event. South Carolina, tracking the language of the model law, requires notice to the state insurance director within 72 hours of detecting a cybersecurity event. The Ohio, Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, New Hampshire, and Mississippi schemes provide that licensees have three business days to report cybersecurity events to the designated state insurance authority. The Michigan statute gives licensees 10 business days to report cybersecurity events to the state director of insurance.

Additionally, although all three statutory schemes contain enforcement provisions, Michigan provides more detailed penalty language for violations. For instance, providing false notice of a cybersecurity event, with the intent to defraud, is classified as a misdemeanor criminal offense, with penalties including imprisonment or fines. Additionally, knowing failure to provide notice of a cybersecurity event may result in a $250 fine for each failure, up to a maximum of $750,000 for multiple failures arising out of a single cybersecurity event.

The Ohio statutory scheme is unique in incorporating a “safe harbor” provision that grants licensees that comply with the act an affirmative defense in tort actions arising under state law and alleging a “failure to implement reasonable information security controls resulted in a data breach concerning nonpublic information.” A licensee that meets the requirements of the Act “shall be deemed to have implemented a cybersecurity program that reasonably conforms to an industry-recognized cybersecurity framework for the purposes of Chapter 1354. of the Revised Code.”