Massachusetts changed its data breach disclosure statute in January 2019. The new statute affects every Massachusetts business that handles personal information about residents of the commonwealth. In other words, the vast majority of businesses. The penalties for violating the statute are significant—up to $5,000 for each violation and up to $10,000 for each violation of any injunction or order issued under the statute.

If other states enact the same or similar disclosure rules and penalties, enterprises outside of Massachusetts will need to adjust their compliance processes, making this an excellent “handwriting on the wall” case study for planning purposes.

The key changes in the statute—which relate to enterprises that suffer a data breach—require that state officials must be told of the nature of the breach, how many residents were impacted, the type of personal information compromised, the status of the company’s written information security program (WISP), and what the victims have done to mitigate the effects of the attack.

On the surface, there’s nothing especially different from what enterprises have been accustomed to sharing. But take note of the WISP reference. It merely asks if a WISP exists and whether it has been updated. A simple “Yes” would seem to comply, but what does saying “Yes” really mean?

How stating “Yes, a WISP exists” may pose risks

If regulators—or consumers who are part of a lawsuit related to the breach—ask to see a copy of your WISP, it now becomes a public document. This shouldn’t be of concern to a CISO since the only alternative is the much maligned “security through obscurity.” If your controls are effective only if they are kept secret, then they are not effective controls.

Your WISP must be detailed enough to keep regulators happy but not so detailed that it might cause them to start probing or be useful to a cyberthief or even a direct business rival. The key is to not overstate your compliance parameters. For example, stating that Web browsers will be kept up to date may be appropriate for a Configuration Standard, but not necessarily as policy, because it may open the company to a finding even if a single computer is found to be out of date.

It can be difficult to know if an enterprise’s WISP will withstand regulatory scrutiny. This is due in part to vagueness in the WISP requirements.

What, exactly, is “appropriate?”

Consider the very first requirement of the Massachusetts regulation (Duty to Protect and Standards for Protecting Personal Information). “Every person that owns or licenses personal information about a resident of the Commonwealth shall develop, implement, and maintain a comprehensive information security program that is written in one or more readily accessible parts and contains administrative, technical, and physical safeguards that are appropriate…”

Who decides what level of administrative, technical and physical safeguards are “appropriate”? Because of vague language, this will likely be determined by individual regulators who may disagree with each other and possibly the courts.

And what is “reasonable?”

In an area of the regulation crafted to make sure companies operating in Massachusetts are keeping security protections current, the “Minimum Standards” require: “Reasonably up-to-date versions of system security agent software, which must include malware protection and reasonably up-to-date patches and virus definitions…”

The vague term “reasonably” is not very helpful in a compliance context. Is six months reasonable? Five days? In an emergent situation, such as the discovery of an especially destructive virus that is specifically and immediately hitting similarly-sized companies in your industry, waiting even five hours may not be reasonable.

Or look at the term “Reasonably up-to-date.” Up-to-date from what starting point? The date the software version was released? The date the version was announced? What if it wasn’t announced and the company was honestly unaware of the version patch for two days?

By using the vague term “reasonably” as its standard for measuring the sufficiency of an enterprise’s information security program, Massachusetts is pushing the determination down the road to a field regulator, or in the case of a lawsuit, a judge or jury. Ideally, stated rules should allow a company to know exactly what steps to take to maintain compliance. Unfortunately, that often doesn’t happen.

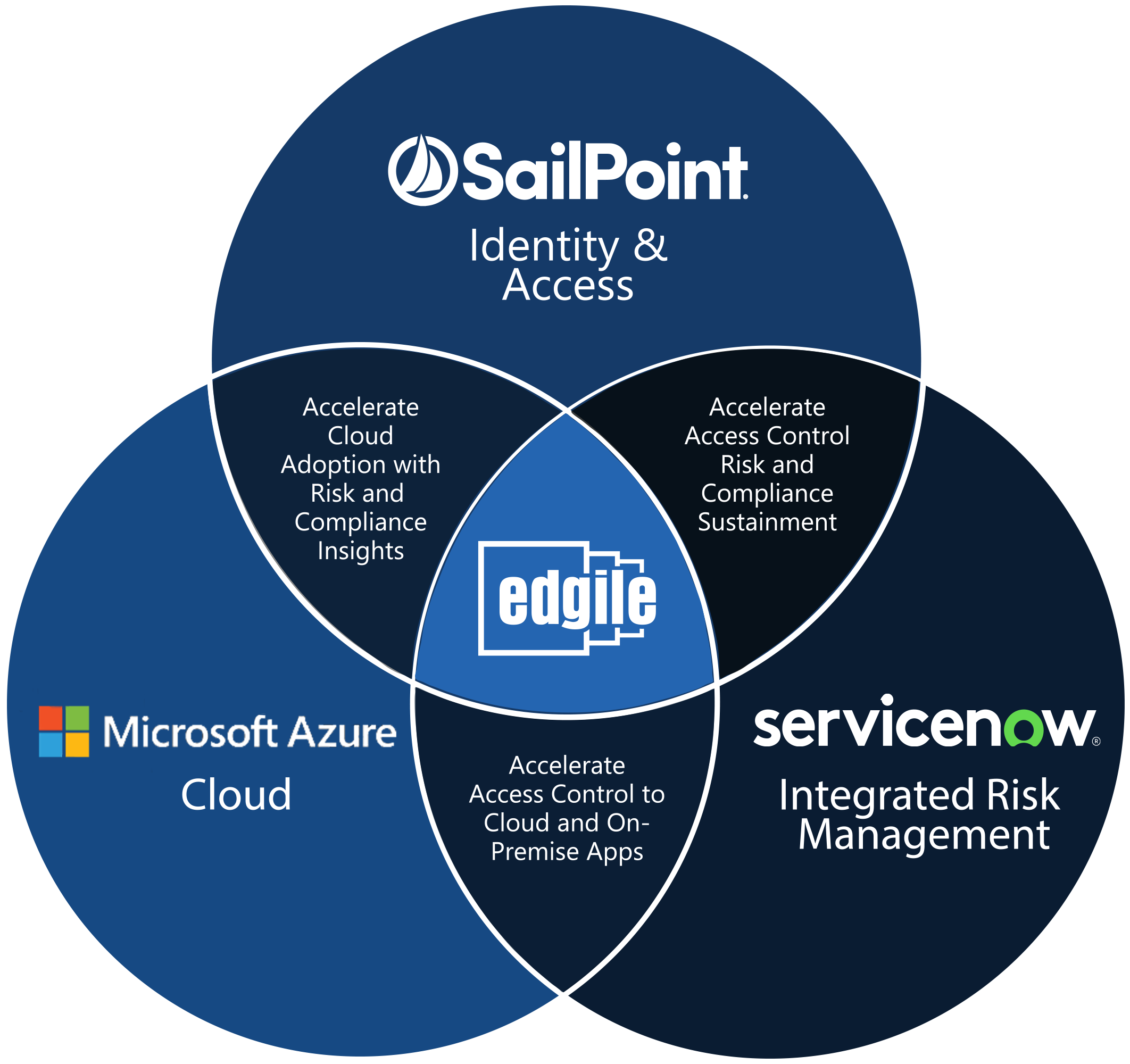

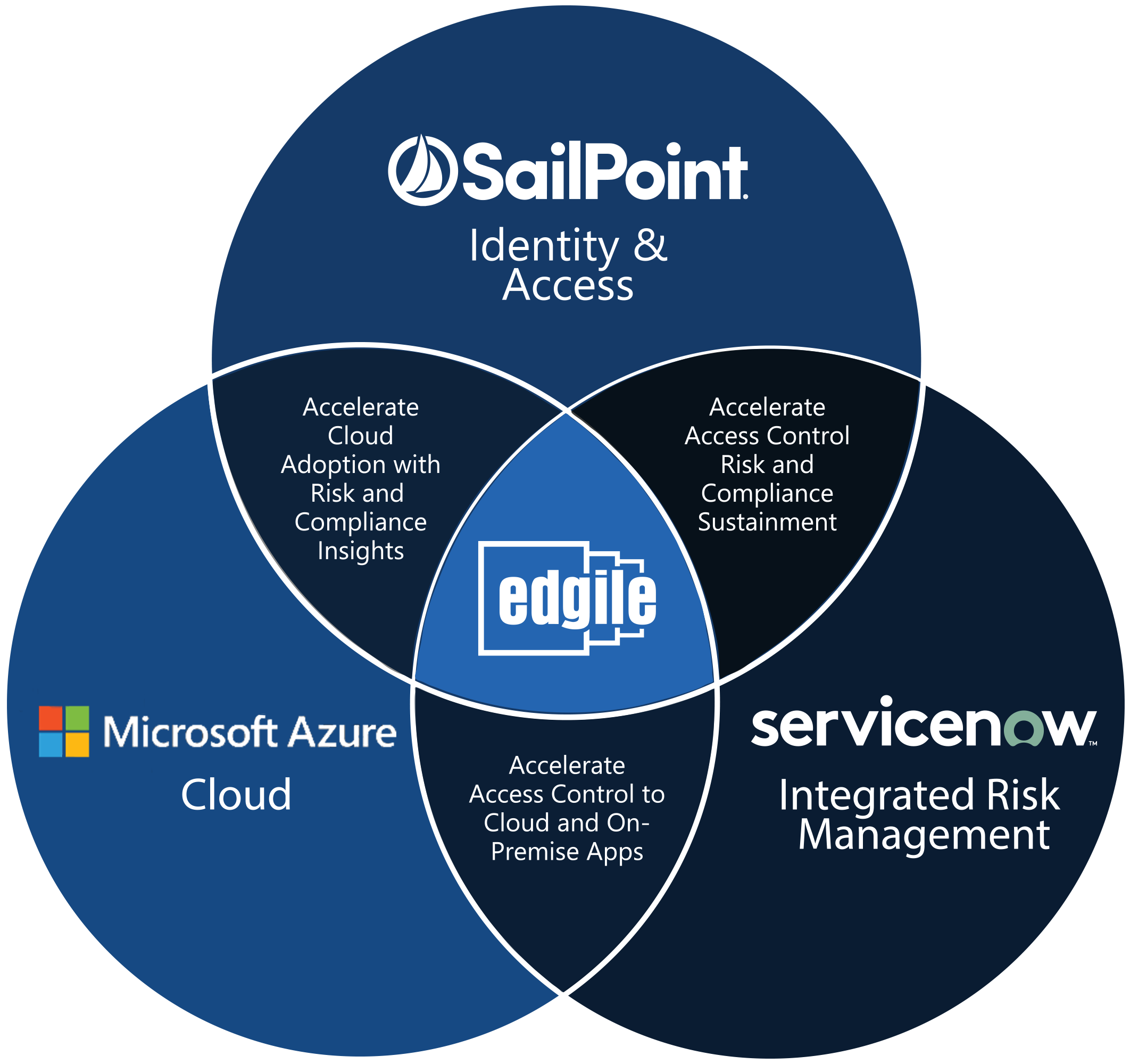

Edgile know how to clarify regulatory vagueness

Vagueness is hardly unique to Massachusetts. It’s found in many laws and compliance standards. Why? Frequently, legislators are engaged in a balancing act: they want to hold businesses accountable while also giving field regulators sufficient flexibility to make decisions on a case-by-case basis.

Many executives not familiar with security may apply a checklist approach to regulatory compliance. Check off all the “things” we need to do and we’ll be in compliance. But rule vagueness makes this unrealistic. Companies need a strategic risk program that specifically justifies why the controls are reasonable.

Controls cannot realistically be applied uniformly across the company. Some systems are high risk and require tight controls, but many are low risk and tight controls in these areas could overwhelm the company. For the most part, regulations do not define high risk vs. low risk but instead leave it up to each company to sort that out. This vagueness can be good as it gives companies the ability to customize their risk controls in ways that are most beneficial to their operations. But as explained above, it creates uncertainty for compliance officers.

To learn more about Edgile’s long track record of successfully helping companies resolve uncertainties around their controls due to vaguely worded regulations, contact Edgile.